A journey into how interdisciplinary endeavours can naturally emerge across different scientific disciplines from theoretical physics and mathematics to health science.

When can we travel again?

Beginning 2020

The prologue

By December 2019 the world was about to face, largely unprepared, one of the deadliest pandemic crisis in human history.

The pandemics exploded in Wuhan China in December 2019 and many of us wrongly assumed that it would have been somehow contained.

I was, in fact, planning a number of research trips including one for a lecture at MIT in Boston and a longer research visit at Yale University. There about two decades ago I had spent three wonderful years as research fellow. Not only had I learnt so much from the wonderful colleagues and senior researchers at Yale but, crucially, also how to function as a fully independent researcher.

After returning to Denmark from a research visit to Napoli, Italy in mid February 2020, Europe was about to become the primary target of the pandemics with epicenter in northern Italy.

As the situation was unfolding we received a message from the University telling that we had to postpone our research trips. However nobody could tell us when we could travel again.

The story

It was then that I felt the urge to understand what was going on, and hopefully answer the question: When can we travel again?

Despite the well known idiom how ”curiosity killed the cat”, I therefore decided to give in to my own curiosity and use my theoretical physics bag of skills to make a dent in understanding pandemic dynamics and evolution.

Often research is more fun when it is shared with colleagues. I was very fortunate to start this endeavor with Michele della Morte, also a theoretical physicist. Michele is part of the centre excellence in theoretical physics of elementary particles and cosmology that I brought to life in 2009 in Denmark and financed by the Danish National Research Foundation. Later on I was immensely happy that one more colleague, Domenico Orlando from INFN, Torino in Italy joined the team.

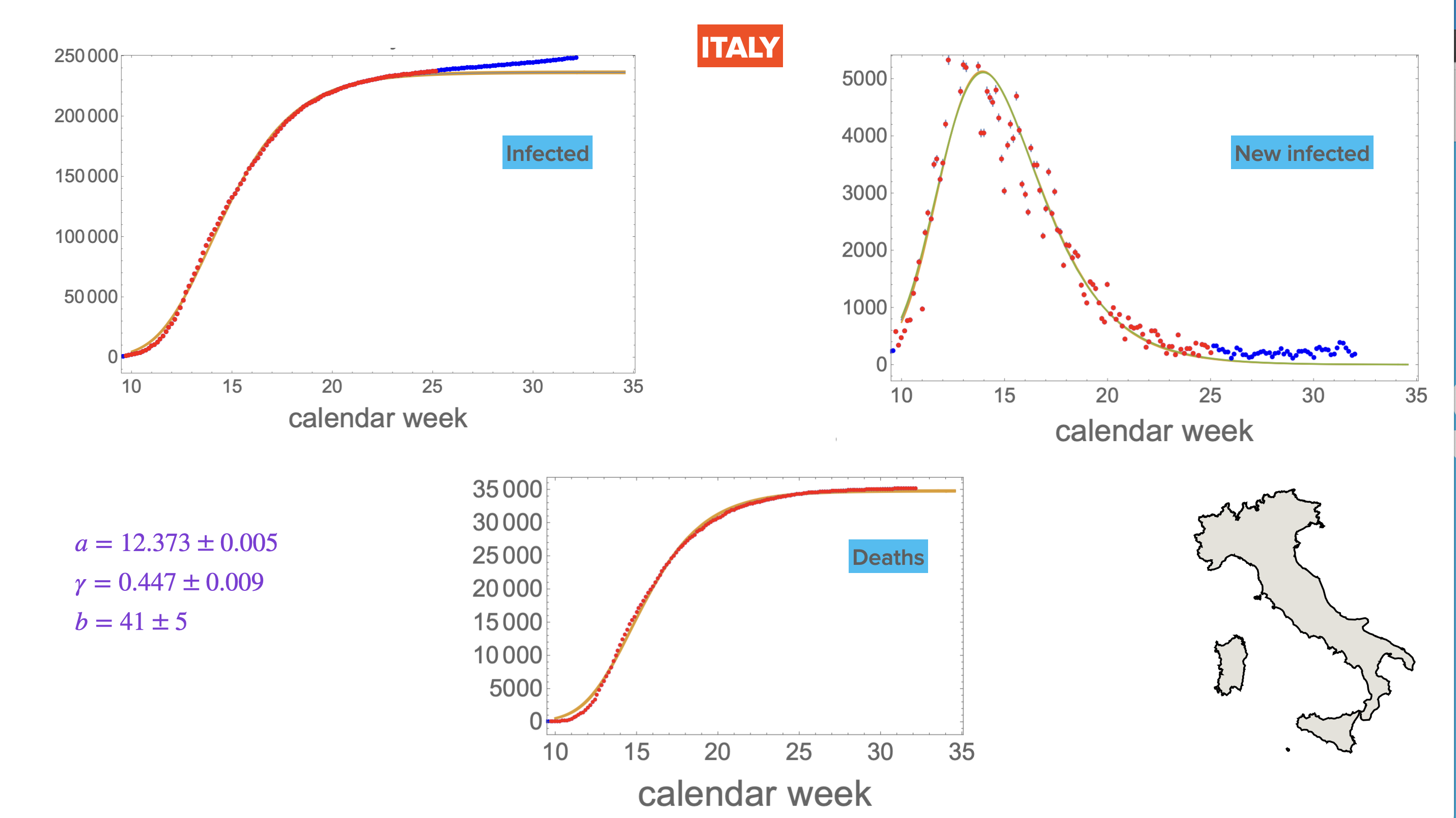

Given that our background was in high energy physics, from Higgs physics to numerical simulations of the strong force and string theory, we had to star from scratch in epidemiology. It seemed reasonable to begin our journey with the data available on the World Health Organisation (WHO) website. We concentrated on the temporal evolution of the number of SARS-COV-2 infected people in China, Korea, Italy and other reported countries.

From the outset, and differently from the bulk of other studies, we decided to investigate the temporal evolution of the outbreaks in various regions of the world. This allowed us to reduce as much as possible the inevitable biases that occur when focusing on restricted regions of the world. At the same time this global approach is better suited to reveal general patterns in the transmission and diffusion of the virus.

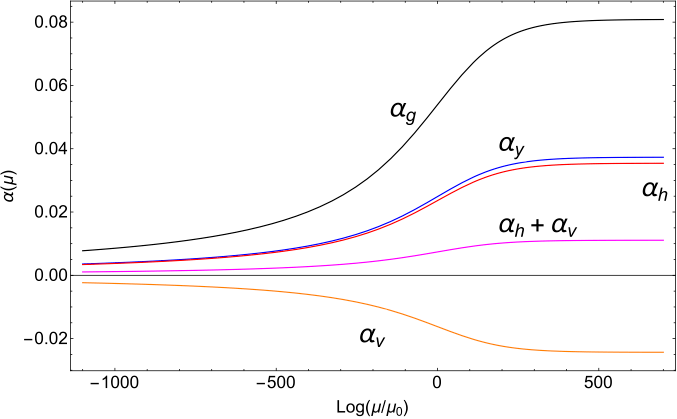

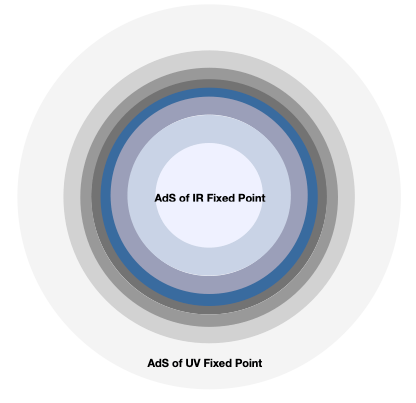

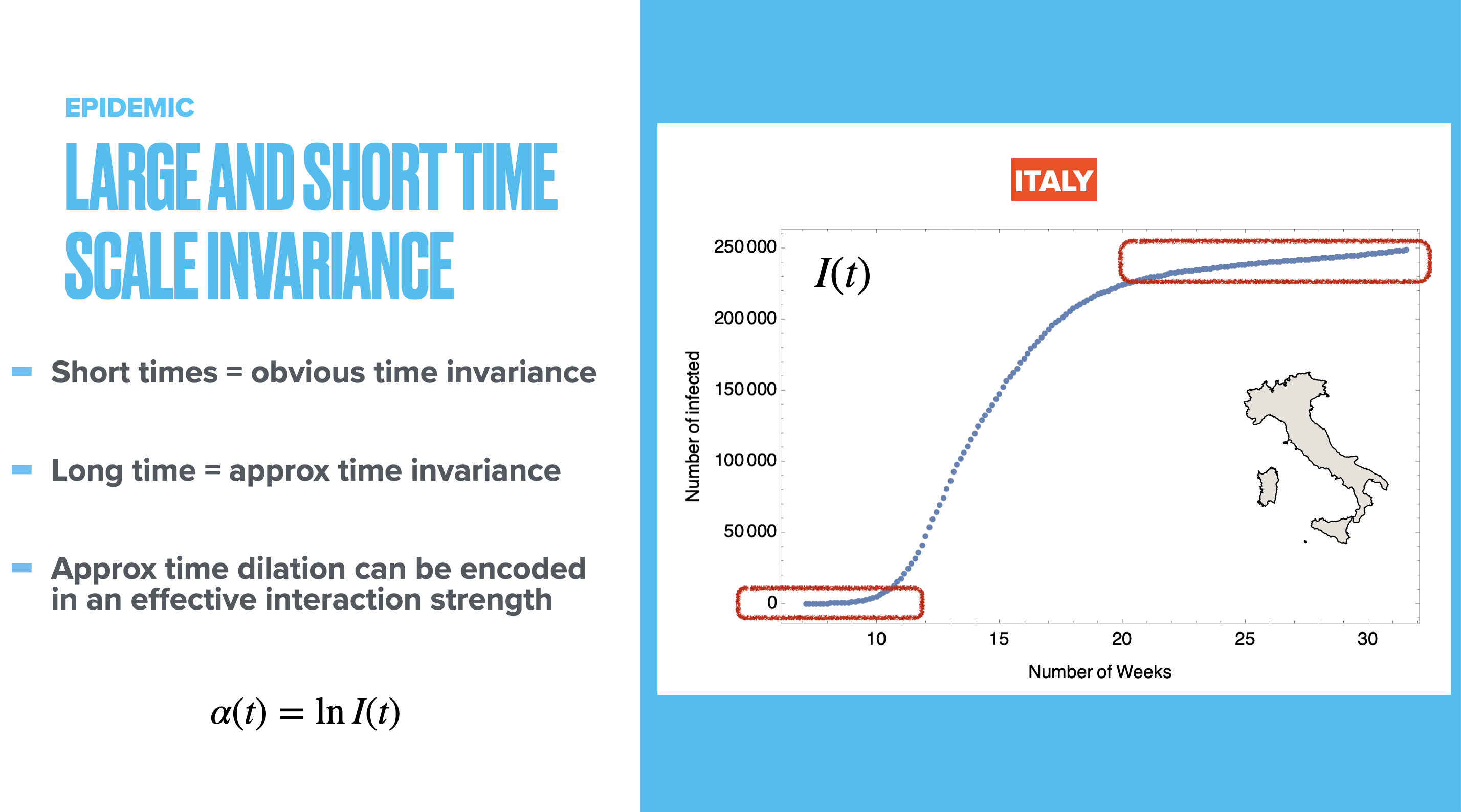

The typical S-shape behavior of the logistic function used to fit the data immediately reminded me of the dynamics of certain physical systems. This dynamics is controlled by symmetry principles such as approximate invariance of the short and large time cumulative number of infected individuals upon a time rescaling. These type of symmetry principles are the pillars on which the modern physics of fundamental interactions relies on, from the physics of the Higgs (discovered in 2012 at CERN ) to string theory, introduced to unify the theory of quantum gravity with the other forces discovered so far. We dubbed the approach Epidemic Renormalization Group (eRG) in honor of the physicist Kenneth Wilson that revolutionized physics with the introduction of the RG approach. The latter is an extremely powerful tool. It is devised to encode the relevant degrees of freedom needed to describe a given physics problem at hand. It is further apt to capture rescaling symmetries via the appearance of fixed points in the theory.

An important step was to further link our work to established mathematical models. We therefore constructed an explicit map between our framework and classical epidemiological approaches. These use various versions of the Susceptible-Infected-Removed (SIR) type of models, which were introduced almost a century ago, and more precisely in 1927, by Kermack, McKendrick and Walker. The crucial difference between SIR and the eRG is that the latter is devised to be reliable on longer time scale than the SIR one.

To our surprise, not only the approach proved efficient in describing and predicting the evolution and spread of the virus within a region of the world, but once opportunely generalized, in collaboration with Giacomo Cacciapaglia, from CNRS in Lyon France and later on also with Corentin COT, PhD student at the University of Lyon, it proved efficient in describing the diffusion across different regions of the world. Since the beginning of August 2020, we predicted by averaging through hundreds of simulations, that the second wave in Europe would take place between the end of August and the first months of 2021. Our simulations and forecasts were designed to prepare governments, industries and citizens of the various European states to take the relevant measures to avoid, delay and/or reduce the impact of the second pandemic wave. Because of the relevance of our results our work was selected by Nature research for an international press release.

Coming back to the initial question, When could we travel again? Already from the first paper it become clear that rather than postponing I had to cancel the trips.

More generally, our work had shown that the eRG framework efficiently captures the temporal evolution of the pandemic diffusion across the globe with only two relevant parameters per each region of the world.

Quite excitingly we also discovered that we could combine mobility data provided by Google and Apple combined with the eRG to quantify the impact of social measures on the evolution of the pandemic worldwide. We were able to determine the impact of the vaccination strategies for the United States pandemic and recently we qualified the vaccine uptake in the Nordic countries and the impact on key indicators of COVID-19 severity and health care stress level via age-range comparative analysis.

Looking ahead

My current interests regarding this exciting line of research is in understanding virus variants genesis and evolution. This is achieved by marrying machine learning techniques to genome data with the epidemic Renormalisation Group framework. One of our recent discoveries is that each pandemic COVID-19 wave has been driven by a new and more aggressive variant and we built an early warning system able to detect new variants of concern in order to control their evolution.

The epilogue

Overall our story is an example of highly interdisciplinary work that is the key of human progress. It seems that curiosity doesn’t kill the cat but ignorance well could have done that.

Part of what I reported here was published early in 2022 in Arkhimedes, a journal of Finnish Academy of Science.